Today is Ada Lovelace Day, a day for bloggers around the world to shine their bloggy spotlights on some tech-inclined women they admire.

I chose three: Erika DeBenedictis, Katheryn Shi and Kate Rudolph. These women are award-winning physicists and mathematicians working to make space travel more efficient, predict the existence of new chemical compounds and decrypt the geometry of supercooled water.

And none of them is older than 18.

These badass ladies were finalists in the Intel Science Talent Search, one of the most presitgious high school science competitions around. The kids in this competition are seriously impressive. Not only do they spend their summers and weekends doing independent research on string theory and machine learning, but they all spent three hours at the National Academy of Science last Sunday explaining their projects to whoever wandered in (including, of course, the judges). They were orders of magnitude more poised and articulate than anyone I knew when I was 18. It’s pretty inspiring.

So without further ado:

Erika Alden DeBenedictis

Erika wrote navigation software that could help interplanetary spacecraft cut down their trips by a factor of 10. Imagine the gravity fields around planets as a topographical map, with hills where gravity pulls strongly toward either the planet or the sun and valleys where the planet’s gravity and the sun’s gravity nearly cancel each other out. Spacecraft can coast along gravitational lowlands–an “interplanetary superhighway“–with surprisingly little energy. But it’s not easy to find and stay on the roads, and current spaceships tend to head in the direction they’re aimed.

Erika wrote navigation software that could help interplanetary spacecraft cut down their trips by a factor of 10. Imagine the gravity fields around planets as a topographical map, with hills where gravity pulls strongly toward either the planet or the sun and valleys where the planet’s gravity and the sun’s gravity nearly cancel each other out. Spacecraft can coast along gravitational lowlands–an “interplanetary superhighway“–with surprisingly little energy. But it’s not easy to find and stay on the roads, and current spaceships tend to head in the direction they’re aimed.

Assuming your spacecraft had an ion engine, Erika’s software can help it shift direction mid-flight and stay on course. Spaceships could travel the interplanetary superhighway like merchant ships traveled ocean shipping lanes. Erika is most excited about the possibilities in the commercial space industry, which she wants to join after studying physics and computer science at MIT or Caltech. The shorter and more fuel-efficient trips her system enables could actually make it profitable to send mining missions to asteroids. (Erika is seriously excited about Obama’s new plan for NASA, by the way. “It gives the private space industry a chance to really do something,” she said.)

I may be biased in favor of cool space travel ideas, but I’m not the only one who liked this one. Erika’s project won first prize.

Katheryn Cheng Shi

Katheryn used computational chemistry (mathematical algorthims that describe the insides of molecules, basically) to predict the existence of two new noble gas compounds, HArN and HKrN. Molecules like this are used in lasers for eye surgery, semiconductor manufacturing and tumor fighting, she said. The molecules are still hypothetical right now, but she hopes to work with synthetic chemists to bring them to life.

Katheryn used computational chemistry (mathematical algorthims that describe the insides of molecules, basically) to predict the existence of two new noble gas compounds, HArN and HKrN. Molecules like this are used in lasers for eye surgery, semiconductor manufacturing and tumor fighting, she said. The molecules are still hypothetical right now, but she hopes to work with synthetic chemists to bring them to life.

Katheryn was drawn to computational chemistry because it was so different from what she thought chemistry was supposed to be like. “I always thought of chemistry as blowing things up, mixing things together, but it’s not really the case,” she said. I thought that was interesting–the image of what science is and what scientists do, especially the images people have in high school, is often pretty far from reality. Some people get turned off when they learn the truth (weren’t you disappointed when you first realized chemists don’t always blow things up? I was), but Katheryn was turned on. It’s great that she came to it so early.

Another awesome thing Katheryn learned early: She earned her second degree black belt in Tae Kwon Do when she was 12.

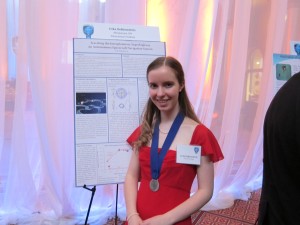

Katherine Rebecca Randolph

When I approached Kate’s poster on presentation day, she was telling a seventh grade girl how awesome it is to be a woman mathematician. “Being a girl opened up so many opportunities for me,” she said–like girls-only contests and competitions whose winners got to go to China. “Totally stick with it, it’s so worth it.”

When I approached Kate’s poster on presentation day, she was telling a seventh grade girl how awesome it is to be a woman mathematician. “Being a girl opened up so many opportunities for me,” she said–like girls-only contests and competitions whose winners got to go to China. “Totally stick with it, it’s so worth it.”

She won my heart then and there, but her project was equally awesome. She studied the best way to make piles of spheres in many dimensions. In the three dimensions we’re used to, the best way to pack spheres is in a pyramid (you can test this yourself with a bunch of oranges). But packing theoretical hyperspheres in higher dimensions is different. The most efficient way to arrange the spheres in eight or 24 dimensions is a lattice, for instance, but in 10 dimensions, the best arrangement is random.

These conclusions have real world applications in chemistry, where scientists try to cool liquid below its freezing point while keeping it liquid–that is, packing its atoms in the most efficient random organization possible. “You have to look at high dimensions, something that’s never going to happen in a real life state, to figure out what’s most efficient in chemistry,” Kate said.

These were just the three projects I looked at most closely. Seventeen of the 40 finalists–and four of the top ten–were women. And having been so publicly recognized as one of the best high school researchers in the country (not one of the best female researchers, just the best, full stop), I bet no one will ever be able to make them feel like they’re not good enough.

Go conquer the world, ladies. I am so looking forward to the rest of your careers.

About a year ago, two scientists from NASA Ames and Carnegie Mellon decided to bring the Mars Rovers’ panoramic photo capabilities back to Earth. The resulting gadget, called a

About a year ago, two scientists from NASA Ames and Carnegie Mellon decided to bring the Mars Rovers’ panoramic photo capabilities back to Earth. The resulting gadget, called a